Headed for Slaughter: China’s Small Abattoirs

Published: Apr 18, 2013

By Michael Pareles, trade manager, USMEF-Beijing

Last month’s press reports of thousands of dead hogs floating in one of Shanghai’s municipal water sources garnered extensive media coverage both in and outside China. Although test results released by China’s Ministry of Agriculture discounted a number of rumors about causes of the mass mortality – ranging from arsenic-based growth enhancers to more common swine diseases – officials have yet to provide a definitive post-mortem diagnosis.

Last month’s press reports of thousands of dead hogs floating in one of Shanghai’s municipal water sources garnered extensive media coverage both in and outside China. Although test results released by China’s Ministry of Agriculture discounted a number of rumors about causes of the mass mortality – ranging from arsenic-based growth enhancers to more common swine diseases – officials have yet to provide a definitive post-mortem diagnosis.

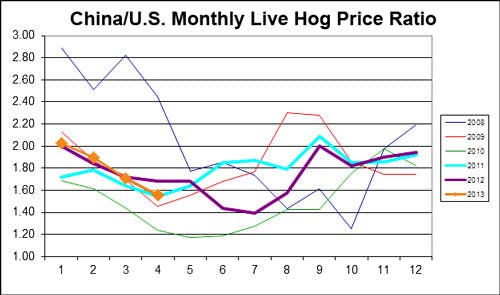

While the difference is narrowing, Chinese live hog prices remain 55% higher than those in the U.S.

Even more unsettling are rumors of a market in which small abattoirs and processing rooms specifically seek out – for a discount compared to healthy market hogs – diseased or dead livestock. In mid-March, China’s official China Daily reported that 46 people had been arrested in Zhejiang Province, near Shanghai, for processing and selling meat from diseased animals. At least one of those arrested was connected with a local meat processing facility.

While the arrests, combined with the thousands of dead hogs, suggest deeper food safety problems, they may actually signal improvements in China’s food safety system.

Since late 2011, the Chinese government has engaged in an aggressive “rectification” of abattoirs around the country – inspecting slaughter facilities nationwide and closing those that aren’t up to code. Already, a coalition of eight ministry-level government departments has announced that 5,218 of the nation’s 19,938 slaughterhouses have been shuttered as part of this effort.

While China has announced a number of campaigns to close illegal slaughter plants since the industry was mostly privatized 20 years ago, the current effort appears to be the most ambitious.

In its latest five-year plan, the Chinese government set the goal of eliminating 50 percent of all non-standard small- and medium-size slaughterhouses. With its most recent announcement, the government has reduced the number 26 percent, so more can be expected to close their doors before 2015.

Most of those closed (and 74 percent of all slaughterhouses in China) are small-scale, non-mechanized operations, the type most likely to be unlicensed and operating below code.

On a related note, it was announced recently that oversight and management of slaughterhouses would be transferred from the Ministry of Commerce to the Ministry of Agriculture. While it is still too early to know if this will bring any changes in the regulation of China’s meat processing industry, it indicates at least that slaughterhouse consolidation is a key aspect of the government’s food safety restructuring.

The closure of small slaughter facilities is expected to provide food safety benefits as China transitions to a more consolidated processing sector. In addition, it is expected to boost the financials of China’s large meat processors. Large processors compete with smaller, more flexible local plants for live hogs, an issue that becomes acute when supplies are short.

According to a USMEF-funded 2012 study conducted by the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), 24 slaughterhouses in the main hog-producing provinces of Sichuan, Hunan and Jilin were found to be operating under capacity – averaging a mere 41 percent of capacity despite China’s abundant hog supply. While the current abundant live hog situation may have helped boost slaughter numbers by all plants (China just reported its 2013 1st quarter pork production is up 2.8% year-on-year), underutilization has been a chronic problem of the industry for years.

A report by Chinese bank Citic Securities projects that the government’s drive to close smaller processors will remove more than $16 billion in assets from the industry, leaving plenty of room for larger producers like Shuanghui, Yurun and Dazhong (People’s) to increase slaughter market share. Although China’s “Big Three” report revenues on par with some of the largest global processors, their collective market share (4.8 percent of slaughter and 17.6 percent of further processing in 2011) remains small, suggesting room for further consolidation.

As regional pork production is consolidated, branding will become more evident, especially for processed meat. One Chinese report estimates that slaughterhouse profits have increased 15 percent because of the most recent rectification push.

Since market leader Shuanghui plans large investments in domestic facilities to fuel international expansion and become one of the world’s three largest producers, China’s slaughter rectification campaign will further increase the global competiveness of its top protein companies.

Currently, live hogs are approximately 55 percent more expensive in China than in the United States. While China may never produce hogs or corn as cheaply as the U.S., policies like this indicate that, at least on the processing side, Chinese slaughter efficiency may increase.